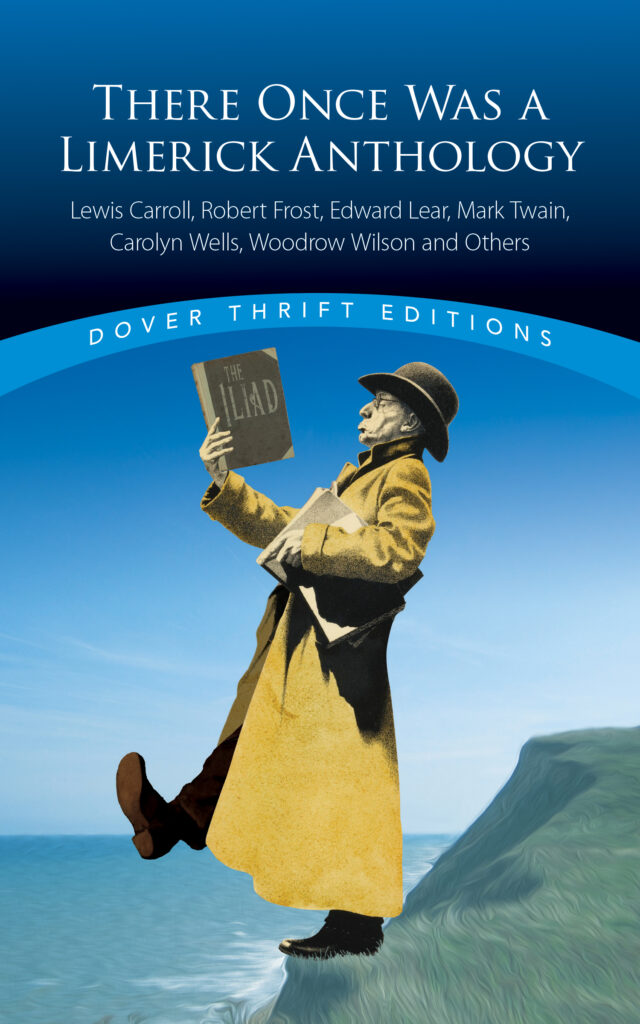

Many limericks have creative misspellings, and in There Once Was a Limerick Anthology (which was published in August by Dover Publications), they appear together in one chapter. I’m usually a stickler for following spelling conventions, but these limericks delightfully break the rules and tickle my funny bone. As I explained in the chapter introduction, “The poets revel in the idiosyncrasies of spelling and pronunciation, showing tremendous love for the English language in order to butcher it so cleverly.”

I continued, “These limericks rely on a pattern. Take note of the conventionally spelled word at the end of the opening line. Then rhyme it with the similarly spelled words, which vary from dictionary-approved spellings. In most cases, the initial rhyming word gives away the pattern. If that word is an unfamiliar proper noun, keep the pattern in mind and look at its partners in rhyme.”

Two of the best-known limericks rely on creative misspellings:

There once was a man from Nantucket Who kept all his cash in a bucket, But his daughter, named Nan, Ran away with a man, And as for the bucket, Nantucket. —Dayton Voorhees A rare old bird is the Pelican, His beak holds more than his belican. He can take in his beak Enough food for a week. I’m darned if I know how the helican! —Dixon Merritt

This approach is taken to a delectable extreme in the following limerick, where “coff” is pronounced “cough” and “cough” is pronounced “cow”:

There was a young lady of Slough, Who went for a ride on a cough. The brute pitched her off When she started to coff; She ne’er rides on such animals nough. —Langford Reed

In the next batch of limericks, all but the first were anonymously written.

A sporty young man in St. Pierre Had a sweetheart and oft went to sierre. She was Gladys by name, And one time when he came Her mother said: “Gladys St. Hierre.” —Ferdinand G. Christgau A maiden of gay Aberystwyth Left her mark on a man she kept trystwyth— Vermilion streaks On his neck and his cheeks— With the paint on the lips that she kystwyth. There once was a doughty old colonel Whose language was something infolonel; He’d swear all the fall At nothing at all, Growing worse when the weather got volonel. Said a careless young smoker named Farquharson, “I greatly dislike the new parquharson. In striking a match I set fire to a thatch. And he threatens to charge me with arquharson.” There lives a young lady named Geoghegan; The name is apparently Peoghegan. She’ll be changing it Solquhoun For that of Colquhoun, But the date is at present a veoghegan. Said a maid, “I shall marry for lucre.” Then her ma stood right up and shuckre, But just the same When a chance came The old dame said no word to rebuchre. There once was a man named McVeagh, Whose greatest delight was to seagh To those who asked why It was not spelled a-y, Just simply, "That isn’t the weagh." There was a young lady named Psyche, Who was heard to ejaculate, “Pcryche!” For, when riding her pbych, She ran over a ptych, And fell on some rails that were pspyche. A pleasant young fellow named Seixas Was thought to be rather audeixas Till he saw a white post Which he took for a gost And ran away, screaming “Good Greixas!” There was a young lady named Wemyss, Who, it semyss, was troubled with dremyss. She would wake in the night, And, in terrible fright, Shake the bemyss of the house with her scremyss.

The selection about violinist August Wilhelmj is the only poem with multiple stanzas in the book. I noted, “There are numerous examples of poems with two or more stanzas in the limerick structure, but it is difficult for the poet to sustain momentum following the fifth line. This is especially true if that line is the punch line in a comic limerick, as the humor typically feels stale afterward.”

Oh, King of the fiddle, Wilhelmj, If truly you love me just tellmj; Just answer my sigh By a glance of your eye, Be honest, and don’t try to sellmj. With rapture your music did thrillmj, With pleasure supreme it did fillmj, And if I could believe That you meant to deceive, Wilhelmj, I think it would kilmj! —Robert J. Burdette

No Comments